Why scientists are monitoring soybeans from space

NASA's latest satellite launch is tied to food security and climate resilience.

Last week, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) sent a new satellite called Landsat 9 into space. And while it didn’t get nearly as much attention as the almost-certainly-pointless billionaire space race, this launch could actually help improve life on this planet in practical, important, and immediate ways.

Specifically, data from Landsat 9 could help prevent food shortages, reduce farming’s negative environmental impacts, and improve farmers’ ability to produce food in the midst of a climate crisis.

It’s the newest member of a family of earth observation satellites that have been circling around us for about 50 years, capturing information on things like crop yields, algal blooms, and wildfires that scientists then use to study the food system. And, according to Alyssa Kathleen Whitcraft, PhD, it’s part of a new era of satellite-driven research that is poised to deliver answers on how to produce enough food in the most sustainable ways.

“There's still a ton of potential yet to be realized, but progress has really accelerated recently… [and] the era we're in now...is facilitating a huge leap forward in the use of these huge data systems for agricultural assessment,” Whitcraft said during a presentation at an agricultural technology and food salon hosted by the International Food Information Council on Wednesday.

In addition to an abundance of quality data, Whitcraft pointed to advances in computation using machine learning and artificial intelligence and the increasing public attention to and urgency around the link between farming and environmental impact. “People are waking up to the reality of climate change and environmental degradation...and they're starting to demonstrate an appetite for transparency and traceability in their purchases of agricultural commodities,” she said.

I’ve been fascinated by NASA’s involvement in farm research for a long time, so I jumped at the chance to share takeaways from her presentation and other recent data on how satellite data is being used to improve the food system.

Unwrapped

NASA launched its first Landsat satellite mission to monitor agriculture in 1972, but the space agency’s farm focus was amplified in 2017 when it formed NASA Harvest with an explicit mission to further food security and environmental resilience. Researchers at the University of Maryland, including Whitcraft, NASA Harvest’s associate director and program manager, run the project, but they work with partners all over the globe.

Whitcraft explained that satellite earth observation—or “remote sensing”—involves tracking much more than what us mere earthlings can see with our eyes. It’s a process of “detecting and monitoring physical characteristics of an area by measuring its reflected and emitted radiation,” she said. “By taking advantage of the full electromagnetic spectrum, we can learn about everything from soil moisture, to active fires, to burn scars, to gravitational changes on earth’s surface, to deformation that's related to seismic activity or aquifer loss...and then also things like photosynthesis in vegetation, which is really important for what I do with crops.” The data is especially powerful because the satellites are essentially able to “image the whole earth pretty much every day,” which means you can detect and capture small changes over time.

So what the heck does taking this data and applying it to food actually look like?

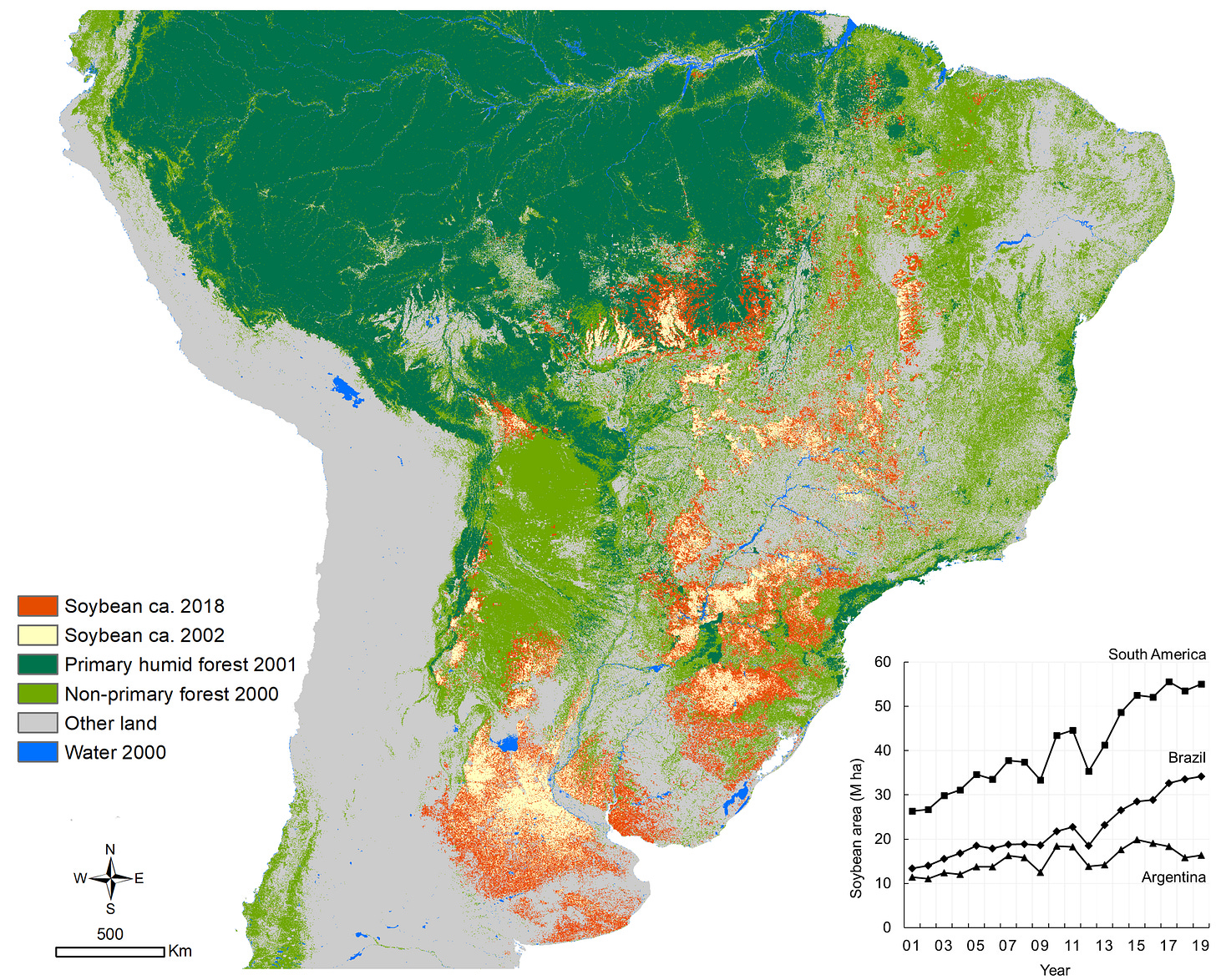

First, NASA Harvest’s projects can simply illuminate what’s happening on the ground and show patterns. For example, experts have used satellite data to track the location and size of algal blooms in lakes and rivers, which are often caused by nutrient runoff from farms. Another recent project mapped the exponential expansion of soybean planting in South America between 2000 and 2019, which could be used as a tool in efforts to stop and prevent further deforestation for farming on the continent.

Satellite data can also be used to assess damages after extreme weather events. After the 2020 Derecho destroyed crops across Iowa, researchers “were able to assess the extent of damage, the degree of damage, and what the crops that were damaged were,” Dr. Whitcraft explained, which helped inform the US Department of Agriculture's disaster response. Her team also helped the government of Togo, one of Africa’s smallest countries, map out where its farmers were in order to quickly get aid to them during the COVID-19 pandemic.

“Another focus for us is ‘early warning’ of acute threats to food security,” she said, as in spotting a region that may be headed for crop failures and heading off a local shortage.

Finally, one of the most exciting prospects for the future involves mapping and measuring conservation practices on farms. NASA Harvest now operates a subprogram called the Sustainable and Regenerative Agriculture (SARA) Initiative, which is trying to fill in gaps in terms of what we know about the climate impacts of practices like planting cover crops and reducing tillage. “We need to build up the evidence base at scale quickly,” Whitcraft explained, in terms of where farmers are using regenerative practices, how those practices are impacting the farm and climate metrics, and how the practices and outcomes differ across different landscapes. One researcher, for example, looked at how reducing tillage affected corn yields across farms and how long it took before those changes happened. You may also remember that earlier this year, I wrote about a study that revealed farmers only planted cover crops on 1 of every 20 acres of corn and soy fields in certain Midwest states; that study relied on satellite data too.

This kind of information is crucial because both governments and corporations are currently rushing to scale up conservation practices on farms. One area policymakers and advocates are excited about is the potential of sequestering carbon in farm soil, but there are still big questions that need to be answered around which practices drive sequestration, how much carbon can be sequestered and for how long, and how factors like geography, weather, and soil type impact sequestration.

It would be pretty cool if data from space could help us figure all that out, right?

Wrapped up, to go

*Satellite data via programs like NASA Harvest can help inform efforts to improve food security and sustainability.

*NASA launched the most advanced Landsat satellite to-date last week, and other advances in technology are also contributing to a new era of satellite-driven agriculture and climate research.

*The data is currently being used to map crop production and land use changes, assess damages to crops after extreme weather events, and evaluate conservation practices.

Still hungry?

Methane emissions from the food system, explained. For Civil Eats, I broke down everything you need to know about how food contributes to emissions of methane, a greenhouse gas with outsized warming potential. The story explains why methane from the food system matters and how it also presents an exciting opportunity for climate action.

Currently devouring

Keeping up with The Jones Act. Alicia Kennedy, one of my favorite food writers (and publisher of her own Substack newsletter), teamed up with her historian partner Israel Meléndez Ayala to write “How the US Dicates What Puerto Rico Eats” for The New York Times opinion section. It’s filled with history, reporting, and analysis on how US policies have crippled local agriculture on the island and supported industrialization that created low-wage jobs and spurred reliance on cheap, unhealthy imported food. Despite all of that, local growers are using their fields to fight back.

Actually eating (well, drinking)

I was in my hometown of Warwick, New York last week and discovered that a new brewery opened just a couple of miles from my childhood home, on a site that was a prison when I was growing up. Turns out The Drowned Lands is a beautiful spot that makes some of the best craft beer I’ve tried in a long time. And I like that the brewers pay homage to the fertile black dirt agricultural region they’ve made their home. If you’re in the area, it’s worth checking out.

Let’s be friends

Follow me on Twitter and Instagram to continue the conversation. See you next week!