Why aren't major restaurant chains taking action on antibiotics in beef?

Antibiotic resistance is a serious public health threat.

In July, Wendy’s announced it would end all routine use of medically important antibiotics in its beef supply by the end of 2030. Groups that have been working to push restaurants to adopt more responsible policies on antibiotics in meat celebrated.

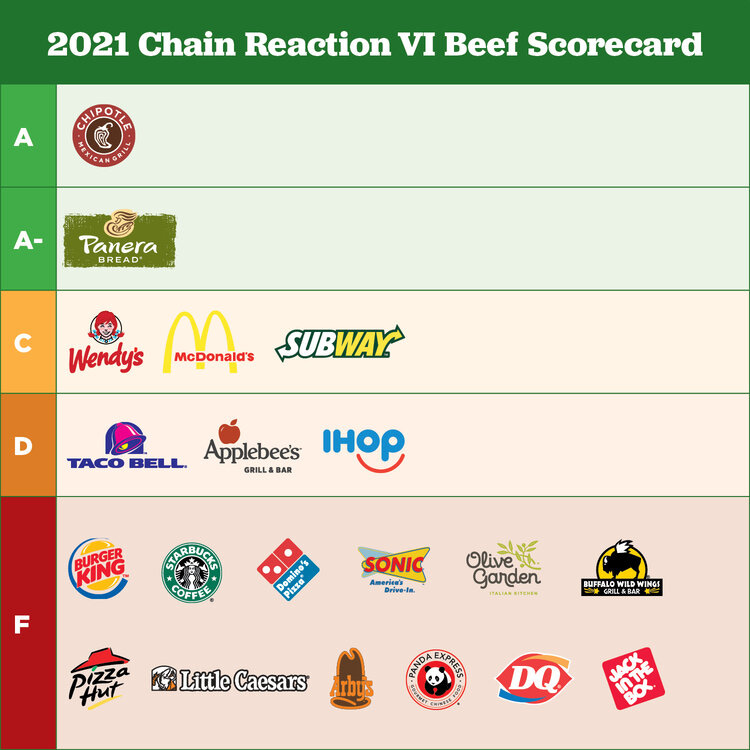

But the announcement came just before the release of the sixth edition of Chain Reaction, a scorecard produced by a coalition of six advocacy organizations that grades the 20 largest fast food chains on those policies—and the scoring was pretty bleak.

15 chains scored a D or an F, and three got a C. All 18 of those are still serving beef from cattle routinely given medically important antibiotics. Just two—Chipotle and Panera—got straight As for real action.

In the past, many of the chains with low marks made announcements similar to the recent Wendy’s pledge, they just haven’t followed through. McDonald’s, for example, said it would set “reduction targets” in beef by the end of 2020, but failed to meet even that deadline. To reiterate: It didn’t miss a deadline to get antibiotics out of its beef; it failed, over the course of two years, to even set a goal for reducing antibiotics in beef. “McDonald’s acknowledged back in 2018 that antibiotic resistance is one of the biggest threats to global health, food security, and development today. So, it is profoundly disappointing that the company is failing to live up to its pledge,” Matt Wellington, public health campaigns director at US PIRG Education Fund, said in a press release.

The groups behind the report acknowledged that many of the chains suffered closures and losses over the past year and a half due to COVID-19 and that those disruptions may have affected progress (or at least whether or not they responded to inquiries about their policies). The coalition delayed the release of the report, which was supposed to come out last spring, for that reason.

But at the end of the day, things would likely not look much different, pandemic or otherwise. As I reported earlier this year for Civil Eats, while the routine use of medically important antibiotics has been dramatically reduced in chicken production, it is still widespread in beef (and pork). And experts agree that if we continue on the same path, many of the drugs we rely on to treat humans could become powerless against antibiotic-resistant strains. According to the CDC, antibiotic-resistant bacteria already cause at least 35,000 deaths in the US each year, and the World Health Organization (WHO) points to antibiotic resistance as “one of the biggest threats to global health” today.

Here’s what you need to know.

Unwrapped

First, let’s get a few things straight. Most experts believe some antibiotics can and should be used to treat sick animals that are being raised for meat on a case by case basis. That’s not what we’re talking about here.

When I say “antibiotics” in this story, I’m referring only to “medically important antibiotics,” meaning they are critical to treating human infections. And when I say “routine use,” I mean the use of these antibiotics is baked into the production process. Medically important antibiotics are administered, sometimes on an ongoing basis, to entire cattle herds in food and/or water. (Again, if you want more details on what this usage looks like, how it breeds resistance, and how it is linked to human health risks, my recent Civil Eats story goes deep on that front.)

Groups behind the report like US PIRG, Center for Food Safety, and the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC) are trying to pressure restaurants to end that kind of use in their supply chains by adopting policies that come closer to aligning with WHO guidelines. WHO “strongly recommends an overall reduction in the use of all classes of medically important antibiotics in food-producing animals, including complete restriction of these antibiotics for growth promotion and disease prevention without diagnosis. Healthy animals should only receive antibiotics to prevent disease if it has been diagnosed in other animals in the same flock, herd, or fish population.”

Chipotle’s policy is a good example of this. According to the report, the company says it doesn’t allow “preventative use” of antibiotics in its meat supply chain. Beyond that, it stated that in 2020, 100 percent of its beef met a “No Antibiotics Ever” standard. Panera has a similar policy to “only allow use of non-medically important antibiotics only for disease treatment under the care of a veterinarian.”

Other than those two, it’s pretty much a given that every other chain represented is serving beef from cattle raised with routine antibiotics. The chains that weren’t given a straight-up F were moved up for having “commitments” that they’ve yet to make progress on or implement.

The reason is simple: beef production systems in the U.S. depend on these antibiotics to keep cattle healthy in unhealthy conditions, and changing those systems is expensive and complicated. While the chicken industry found it was possible to move away from routine antibiotic use while making relatively minor tweaks to their overall systems, experts say the beef industry would have to totally change its ways. Panera provides an interesting case study: The company stated in the report that 99 percent of the beef it sourced in 2019 was 100 percent grass-fed. So it makes sense that it got to antibiotic-free—not by sourcing beef from feedlots that stopped administering the drugs, but by sourcing a totally different kind of beef, from cattle that skipped the feedlot entirely.

Still, the report authors believe that since restaurant chains buy so much beef, they have the power to put pressure on industrial meat companies to make real changes. The point of the scorecard is to get consumers to pressure the restaurants so the restaurants will feel like they have to pressure their suppliers.

“Consumers are concerned about antibiotics losing their effectiveness and want restaurants and meat producers to adopt more responsible practices,” Michael Hansen, a senior scientist at Consumer Reports, said in the Chain Reaction press release. “Fast food restaurants have tremendous market power and can help address our antibiotics crisis by requiring their beef suppliers to stop misusing these life-saving drugs.”

Wrapped up, to go

*Most of the biggest fast food chains are still serving beef from cattle produced with the routine use of medically important antibiotics, with the exception of Chipotle and Panera.

*A few have made commitments to reducing antibiotic use in their beef supply, but the jury’s out on whether those will lead to real action.

*Antibiotic resistance, which the routine overuse of antibiotics in animal agriculture contributes to, is a global public health threat.

A side of policy

The end of the line?? Yesterday, the EPA announced it would issue a final ban on chlorpyrifos—a common pesticide linked to brain damage—in agriculture, ending a long battle over the chemical’s use. After an initial 2000 ban on household use, the EPA under President Obama recommended all uses should cease based on the strong science on its negative health impacts. Under President Trump, the agency ignored that recommendation, and the issue ended up in the courts.

Currently devouring

Oyster magic. I loved this New Yorker profile of Kate Orff, a landscape architect who works with nature to design landscapes for climate resilience. The story is focused on her project using oysters and other natural buffers to protect New York City’s coastal communities from rising seas. It’s the kind of ecosystem-focused thinking that I think the food system and agriculture could use more of.

Afghanistan. This is a little off topic for this newsletter, but it’s hard not to think about the situation in Afghanistan constantly right now. So, I thought I’d at least share this list of resources Time put together on how to help.

Actually eating

Way back in May, I planted vegetable seedlings from a local farm called Two Boots, plus some others I took home from the farm I was working at, Karma Farm. I don’t have a ton of outdoor space and most of it is extremely shaded, so I’ve had to get creative with planting. My tomato plants have been slow to bear fruit because they’re not getting enough light, but they’re finally producing beautiful cherries and a few juicy heirlooms. I’ve also harvested a few peppers, scallions, basil, and Japanese eggplants.

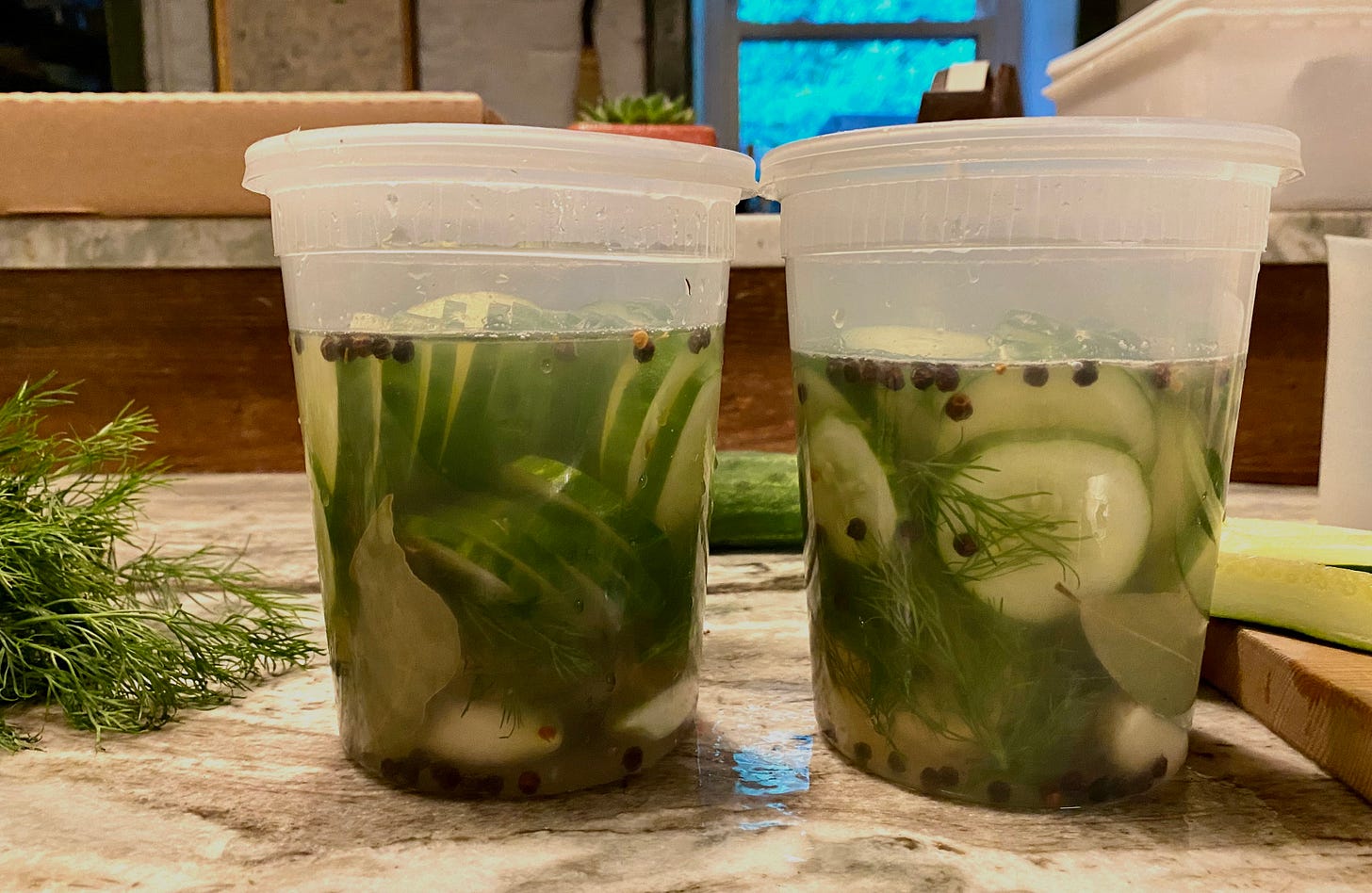

But the cucumbers…oh the cucumbers! I planted two tiny seedlings in the sunniest spot in front of my porch so that I could carefully trellis them up the railing as they grew. And grow they did. To date, I’ve harvested 60—that’s SIXTY—cucs off these two tiny plants, some of them oversized, and they’re still producing. My diet for the past few weeks has involved endless variations on a cucumber salad, cucumber sticks with hummus, cucumber water, gazpacho, etc. I’ve given away at least 20 to family, friends, and neighbors. Finally, this week, I made pickles, using this recipe as a guide.

Growing food, my friends, is unpredictable and involves cycles of scarcity and abundance. Such is life.

Let’s be friends

Follow me on Twitter and Instagram to continue the conversation. See you next week!