When farms curb water pollution, climate benefits follow

A new Chesapeake Conservancy report points to the carbon-holding potential of practices developed to clean up the Bay.

Runoff from Midwest farm fields is a major contributor to the annual “dead zone” in the Gulf of Mexico, and this year, the Connecticut-sized swath is 1,000 square miles larger than scientists predicted. Meanwhile, the latest report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) found that the planet is warming even faster than expected and addressing emissions from agriculture (specifically methane) will be necessary to avoid climate catastrophe.

So yeah, not the best news week for our food system and the environment.

Except...in the midst of it all, Chesapeake Conservancy released an interesting report that relates to both of these problems, on a smaller, local scale.

The report analyzes how on-farm efforts to improve water quality in Virginia’s portion of the Chesapeake Bay watershed are simultaneously removing carbon from the atmosphere. It found that in 2019, changes farmers made to reduce runoff resulted in nearly 460,000 tons of CO2 equivalents sequestered.

To be very clear, the most important thing the IPCC report emphasizes is that scientists agree the only way to truly avoid planetary disaster is to rapidly transition away from fossil fuels. The other stuff is good (and maybe even necessary at this point), but it has to be extra, on top of that first priority.

“As we tail down greenhouse gas emissions, these carbon removal actions can offer further reductions, as it takes time for the reductions in emissions and transportation and energy sectors to take effect,” said Susan Minnemeyer, VP of technology at Chesapeake Conservancy, who worked on the report. “In my mind, it's all part of doing everything you can to reduce the risks of climate change, using all the tools in your tool shed to fight the problem.”

But Ben Lilliston, the director of rural strategies and climate change at the Institute for Agriculture and Trade Policy, said one of the dangers of emphasizing carbon sequestration is that the measurements are still far from precise. He’s also opposed to carbon markets, which the report touches on, because evidence so far shows selling offsets in exchange for sequestration does not lead to real emissions reductions. “It is definitely true that agricultural practices that protect water quality are also valuable in building climate resilience. Building soil health helps farmers withstand extreme weather events in particular, and the [practices] they are referencing also can sequester carbon,” he said. “The problem is linking these efforts to offsets for polluters.”

Another thing that interests me about the report is that I’ve covered a lot of climate solutions that involve trade-offs. Does it make sense to cut down carbon-holding forests to build massive ground-mounted solar systems, for instance? Well probably not, but companies seeking quick profits will always make that case. Reports like this one point to the idea that it is possible to prioritize more than one positive impact at a time. Maybe biodiversity, water quality, and climate could be considered in tandem; so could food waste, hunger, and climate.

Here’s what this analysis of one state’s farm practices means for a more climate-positive food system.

Unwrapped

For decades, a coalition of states, federal agencies, and non-profit organizations have been directing energy and resources towards cleaning up the Chesapeake Bay, which has its own annual dead zone. Since nutrient runoff from farms (across six states) represents the largest source of Bay pollution, many of those efforts have supported farmers in implementing conservation practices that reduce that runoff.

Picture Dave McLaughlin introducing diverse crop rotations and cover crops and ending tillage on his cropland in central Pennsylvania. Or Keith Ohlinger building up his silvopasture operation, which involves grazing cattle in lush pastures planted with trees that form fences and provide shade for animals, in central Maryland.

The practices are designed to prevent nitrogen and phosphorus from leaving fields and making their way into the Bay, and many involve putting and leaving more plants in the ground. Those plants—like trees and legumes—can hold carbon both above and below the ground. They can also add it to the soil.

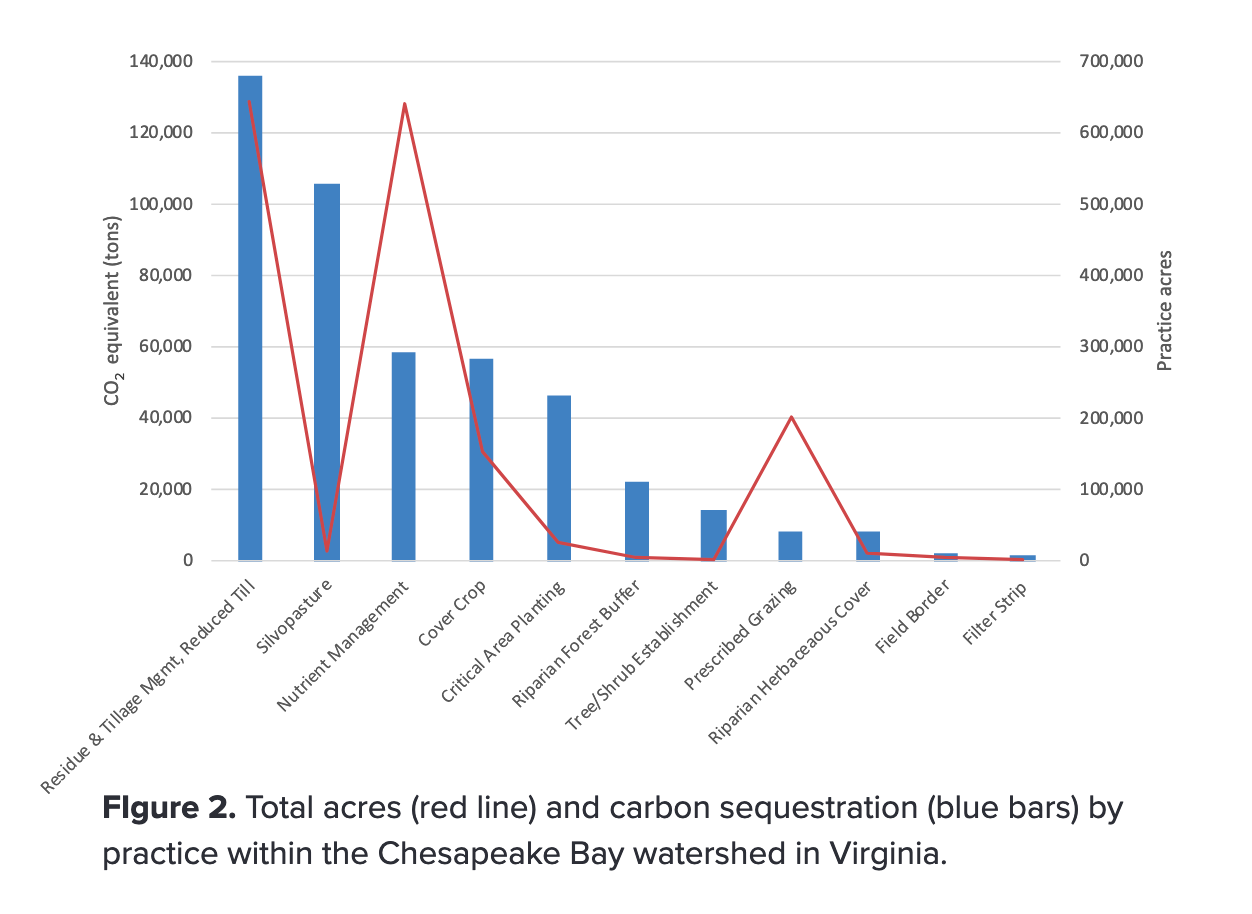

Minnemeyer and her team set out to measure just how much. They calculated the carbon sequestration value of actions taken under the 2014 Chesapeake Bay Watershed agreement, using data reported to the Chesapeake Bay Program and a tool provided by the US Department of Agriculture. The findings: “459,639 tons (416,987 metric tons) of CO2 equivalent were removed from the atmosphere in 2019 by these conservation practices,” equal to approximately 50,000 homes’ electrical use for one year or the annual carbon sequestration of 510,000 acres of average U.S. forests.

That sounds like a lot, but the other comparison the researchers gave is that the savings were equal to just 0.4 percent of Virginia’s energy-related CO2 emissions. So, is it even significant?

Minnemeyer said that first of all, the estimate is conservative and the real number is likely higher, because of limitations in the data that didn’t allow the analysis to include certain practices like wetland restoration, urban tree planting, and nutrient management in animal agriculture. Even as it stands, though, she thought the number represented an impressive starting point.

“I mean, this is how much Virginia is sequestering carbon as a side benefit of trying to protect water quality. I think it shows that there's a really great opportunity to increase that number a lot if you really focus on those practices that both maximize water quality benefits and sequester carbon,” she said.

For example, the analysis showed that reduced tillage accounted for an outsized portion of the carbon sequestration just because farmers were doing it on the largest number of acres. But practices like riparian forest buffers (trees and bushes planted along streams to stop runoff) and silvopasture deliver way more bang for their buck per acre. Encouraging more farmers in that direction then could be “the biggest low hanging fruit in terms of increasing carbon sequestration,” she said. “Silvopasture is really interesting because it offers climate resiliency benefits as well, because when you increase tree cover on pasture you also are providing shade for grazing animals, and that is going to be increasingly more important with a warming climate.”

Not so fast, though. All of the numbers on sequestration are based on modeling that many scientists say is still flawed, or that at least involves too many unanswered questions as of right now. In soil, it’s unclear how long carbon might stick around or how much can be stored before things level off, and the science is changing quickly. Plus, “climate change itself is affecting our ability to sequester carbon,” Lilliston says. What if, for example, wildfires or floods destroy trees and other plantings?

“The latest IPCC report raises some questions to consider—pointing out that our ability to use land and water as a carbon sink is not unending, that it diminishes as carbon dioxide builds in the atmosphere, and that it is not a one-for-one, meaning pollution from a smokestack is not the same as carbon sequestered,” he said.

With that in mind, it’s a good idea to recognize the climate potential of these farm practices, “but they should not be linked to polluters who need to urgently reduce emissions,” via carbon markets. In contrast, Chesapeake Conservancy’s report presents carbon markets as a positive opportunity for farmers in Virginia.

Regardless, everyone agrees these kinds of farm practices are key for helping farmers weather increasing climate storms. And Minnemeyer said that the existing resources and infrastructure around cleaning up the Chesapeake Bay provide states like Virginia with an opportunity to lead on improving food production in a way that’s good for both water and climate.

“We documented practices on 1.6 million acres of land [out of about 5 million farmland acres]. That's quite a large portion. Every farmer will have neighbors that are participating in the program, and I think that word-of-mouth connection and the local connection is really important for enrolling new farmers,” she said. “I think you could scale a lot faster in Virginia than you might in a part of the country that has much lower adoption of these practices.”

Wrapped up, to go

*Many farm practices that improve water quality can also improve farm resiliency as the climate changes and hold carbon.

*A new report quantified those benefits in the state of Virginia, based on Chesapeake Bay clean-up efforts, and found there’s current value and potential to do much more.

*The science on carbon sequestration is still developing, and so far, offset schemes related to sequestration have not led to real reductions in overall greenhouse gas emissions.

Still hungry?

The future of organic. For Foodprint, I wrote about how advocates are fighting to ensure the USDA organic seal still represents what it’s supposed to represent, and how current political leadership might impact those efforts. Some of the big issues are around animal welfare standards and cracking down on fraudulent grain imports, among many others.

Currently devouring

110 degrees. At this very moment, farmworkers in the West are working through extreme heat, fire conditions, and COVID-19 outbreaks. I’ve been thinking about it a lot, but of course it’s nothing new: The story of farm labor in the US is essentially a timeline of exploitation. Photographer and writer David Bacon has covered the lives of farmworkers for years in a way no one else has, via intimate photos and stories that center the narrative around their experiences, ideas, and actions. This week, he published a must-see photo essay that documents how climate change is impacting the lives of farmworkers in the San Joaquin Valley. I also discovered this interview with him, and while it’s a few months old, it’s definitely worth reading and is more relevant than ever.

Actually eating

I ate a lot of amazing food from incredible farms and makers while in Vermont. This is a photo of a pork chop from Mangalitsa, a restaurant in Woodstock. The restaurant has its own farm, where it raises pigs (Mangalitsa is the breed) and grows vegetables like the carrots and fennel pictured here.

Winding Brook Farm, a diversified organic farm with vegetables and livestock, was just down the street from our house, so we stopped at the farmstand often. We went to Roma’s Butchery—where butcher Elizabeth Roma only sources whole animals from local farms—multiple times. I also ate a lot of ice cream from Strafford Creamery, a local organic dairy making its own products. If you ever find yourself in central Vermont, enjoy!

Let’s be friends

Follow me on Twitter and Instagram to continue the conversation. See you next week.