What a 40-year experiment can tell us about organic food

Takeaways from Rodale Institute's Farming Systems Trial.

In Eastern Pennsylvania, fields of corn that stretch endlessly towards the horizon are a common sight. But 12 acres in Kutztown are nothing like the rest.

It’s the site of Rodale Insititute’s Farming Systems Trial (FST), the longest running side-by-side comparison of organic and conventional farming in the world. There, neat rows are being treated differently than their neighbors, while scientists measure and track their performance on several different metrics.

This year, Rodale—a trailblazing force for organic and regenerative farming in the US—is celebrating the trial’s 40th anniversary. Over those four decades, the experiment has produced a wealth of data and has had a broad impact. It influenced the creation of the United States Department of Agriculture’s organic certification program and inspired other research trials around the world. (Side note: FYI, George Washington Carver was pioneering organic soil-building techniques 70 years earlier, and his contributions are often left out of organic’s history.)

Even if “fertility sources” and “crop yields” make your eyes glaze over, the research could affect how you eat. For instance, it might impact the amount of organic food that is produced and available, the price of organic food, and what we know about whether or not organic is better for your health and the planet’s.

“It was really important that we create a uniform certification standard and have a federal law to support it,” said Jeff Moyer, who has worked at Rodale for almost the entire length of the FST and is now CEO. “Now we're saying that we can use the same data sets to drive the conversation around water quality, carbon sequestration and climate change, and also human health. There are so many opportunities there.”

To acknowledge the anniversary, Moyer spoke with me about some of the most significant findings from the FST.

Plenty of food, healthy soil

Rodale researchers launched the FST in response to a USDA survey in the 1980s, Moyer explained. The survey found that one of the main reasons farmers were reluctant to transition to organic was that they worried about sources of nitrogen. Nitrogen is the most essential nutrient for plant growth, and conventional farmers use chemical fertilizer to deliver it. That’s not allowed in organic, and organic sources—manure, compost, or plants that fix nitrogen into the soil—are trickier. Farmers didn’t think they’d be able to provide enough or that it would be more expensive. And at the time, they weren’t being paid more to produce organic food.

Rodale researchers decided to measure how crops given nitrogen in different ways—via chemical fertilizer in a typical conventional system or via manure or planted legumes in an organic system—performed. According to Moyer, they chose to focus on grains in an attempt to influence the maximum number of acres.

“We could have worked on a vegetable experiment, but quite honestly, if you impact the way rutabagas are grown, you're only impacting a really tiny amount of acres, whereas if you can demonstrate positive changes around corn or or even wheat, you can impact millions and millions of acres,” he said. (Among organic advocates, this is one approach. Others believe making changes to a system set up to grow too much of the wrong crops can prolong the life of that system, when it would be better to disrupt it and replace it with diversified organic operations that operate from a completely different paradigm. In a story I wrote about Rodale’s latest partnership for Civil Eats last week, you can see that tension surfacing.)

So nitrogen was the genesis, but the FST gradually transformed into an experiment that went far beyond. “The first first thing we found was that we could actually produce equal yields in organic systems to conventional, even without animals. The other thing we found was that animals in the system made things much easier,” Moyer said. In other words, organic farmers wouldn’t necessarily have to sacrifice yields (i.e. grow less food per acre) when they switched to organic nitrogen sources like manure. Other studies have found the opposite, but Rodale researchers say that’s a function of time. Most studies are short, and when farmers switch to organic, yields do drop—in the first five years. But the FST has shown that over 40 years, the soil bounces back and things level off. Organic fields in the trial have also been able to weather periods of drought much better than conventional.

Of course, Rodale was established to advocate for organic, so we’ve got to keep that in mind. Their researchers have an interest in demonstrating positive outcomes, and the question of yields is still debated. It’s also increasingly important, given how it relates to climate change impacts.

Soil health and climate change

What does the amount of food produced have to do with climate change? If you produce less food on the same amount of land, it follows that you might need more land to feed people. Therefore, greenhouse gas emissions could be increased from the clearing of forests on that land. This is the most common argument cited in studies that find organic farming is “worse for climate change.”

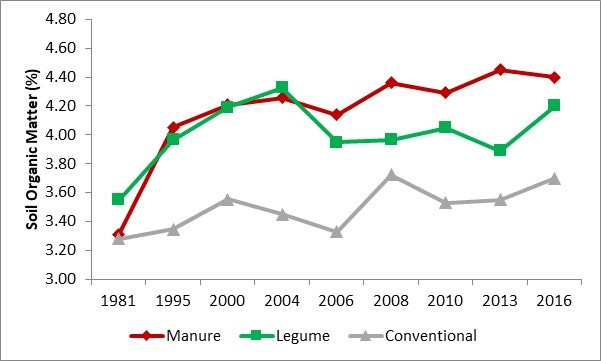

But there are so many factors that contribute to climate impact, and data from the FST also shows impressive increases in organic matter in the soil compared to conventional fields. Check out the graph above.

This matters because organic matter is where carbon hangs out. As in, the carbon that is causing mayhem above ground as a greenhouse gas can be stored beneath our feet, and other long-term farm trials in Maryland, Pennsylvania, and California have all found higher levels of carbon in organic soils, especially deep down where it’s likely to stay for longer periods of time. There are many questions remaining on how to best sequester carbon in soil and whether the amount could be meaningful in terms of slowing down climate change, but this research is promising. Plus, healthier soil benefits farmers in other ways, especially in terms of holding water during droughts.

“Carbon is the currency that helps us build up health,” Moyers said. “As we improve our soil health, we are also able to adapt to the impacts of climate change. One story that we can tell from the FST is that we can improve soil health by the way we farm. 25 years of continuous [conventional] corn had killed that soil. We were able to take that soil and regenerate it. And we didn’t have to take it out of production. You can have marketable crops off of every acre every year and improve the soil while you do it. That's the real bright spot.”

And yield and soil health are only two metrics in a system that includes so much more. While the climate crisis is the most pressing environmental problem facing humans today, organic advocates say that when planning and evaluating research, it’s essential to consider all of the effects, from pesticide impacts to nutrient content. More importantly, Moyer said, is remembering that all agricultural questions should be asked in the context of what the true endpoint is. In other words: What, in the end, is the point of farming?

“If the goal is to ask ‘How do we kill weeds or manage weeds most efficiently and effectively?’ then herbicides work. But that's not the goal of agriculture, right? That’s one step in a process that [should] produce healthy food for healthy people and a healthy planet,” he said. “We’re not suggesting that conventional doesn’t work. If the goal is to produce tons of stuff, it works. We’re suggesting that it doesn’t work if the end goal is human health and planetary health.”

A side of policy

Free lunch. Will it become a new reality for kids across America? In 2019, 22 million children from low-income families qualified for free or reduced-price lunches. During the pandemic, issues with getting the meals to kids at home shone new light on the logistical hurdles involved in determining if and when kids qualify. That prompted a renewal of a long-simmering national movement for “universal school meals,” which I wrote about for Civil Eats in June. Now, The Counter has the story on how that movement is picking up more momentum with a new Congress in place, while California could become the first to pass a universal school meals bill at the state level.

Still hungry?

Meat and me. Yale University (fancy, I know) is hosting a Food Systems Symposium next week. It’s free to register and there are several interesting panels. I’m participating in one on Thursday February 25 called “Building Resilient Meat Supply Chains.” We’re going to be talking about the effects of consolidation in animal agriculture, and according to the organizers, “Our panelists will consider what American agriculture can do to re-imagine an industry that is good for the worker, rural economies, animals, and the planet.” Wow, I’ll do my best!

Currently devouring

Fossil fuels, jobs, rural America…this Medium story by Sarah Mock is about declining oil and gas revenue in Wyoming. But it’s also about how states view and tap natural resources, opportunity in rural towns, and, most interesting to me—how stories about all of those things are told.

Actually eating

An unromantic story about Valentine’s Day brunch: I decided to make a frittata, got all of the ingredients ready, and then realized the feta looked a little sad. I tasted it, and it was really sour, not in a good way.

Instead of serving my beloved a meal made with cheese gone bad (although I did make him try it to confirm it was unusable…whoops), I threw it in the compost and grated cheddar instead. Ingredients: Eggs, scallions, cheddar, kale, pepper flakes, salt. A little saute, bake, voila. Microgreens for garnish on top (unnecessary, but I had them). This is why I love frittatas. You can throw anything in them and they’re almost always good. Just maybe not rotten feta.

Let’s be friends

Follow me on Twitter and Instagram to continue the conversation. See you next week!