For most people, Valentine’s Day came and went this month without attention to the fact that while heart-shaped chocolates were being gifted and enjoyed, the United States Supreme Court was considering who should be held accountable for the child labor (and in this case, slavery) involved in producing them.

In December, the Court heard arguments in a case initiated on behalf of six Malian men who were kidnapped and forced to work long hours on Ivory Coast cocoa farms as children and who are seeking damages from Cargill and Nestlé USA.

The men are six among millions. For decades, the biggest global chocolate companies have raked in profits by building and relying on supply chains filled with child labor. Some children do dangerous work on their families’ farms; others are trafficked. It’s a well-documented fact and is a continuation of the colonialist pursuit of cocoa.

The companies’ lawyers argue that their clients are not to blame, because the abuses are the fault of traffickers in Africa. They say chocolate CEOs abhor child labor and the traffickers should go to jail.

I get it: The players with all the resources and power in this scenario couldn’t possibly figure out how to make sure children aren’t enslaved or abused during the making of their products. It’s a lot to ask of companies with billions of dollars at their disposal, especially when so many people want to give them more money for more cheap chocolate. Plus, you’ve got to sympathize. A 2019 Washington Post investigation found that “Mars, maker of M&M’s and Milky Way, can trace only 24 percent of its cocoa back to farms; Hershey, the maker of Kisses and Reese’s, less than half; Nestlé can trace 49 percent of its global cocoa supply to farms.” How could they possibly take responsibility when they don’t even know where their chocolate is coming from?

Sorry, the sarcasm is a little much, I know. But it’s hard to report on this particular topic without a touch of anger surfacing.

20 (that’s twenty) years ago, these companies—Nestlé, Hershey, Mars, et.al.—signed an agreement concerning “the prohibition and immediate action for the elimination of the worst forms of child labor.”

The aforementioned Washington Post investigation, published less than two years ago, found that child labor was still widespread. And last fall, researchers at the University of Chicago published the results of a five-year study commissioned by the US Department of Labor. They found that the prevalence of child labor in cocoa production in Ghana and Ivory Coast increased by 14 percent over the last decade (leading up to the 2018-2019 harvest season). In 2019, 1.56 million children were engaged in child labor. 95 percent of them were exposed to at least one type of “hazardous” behavior, like using sharp machetes or exposure to toxic pesticides.

(To be clear: This study looked at children living in agricultural households, not trafficking. The two are separate but entangled issues. More children engaged in child labor are working on their families’ farms, but the Post found trafficking is also prevalent.)

So these companies epically broke their promises, and one thing history tells us is we shouldn’t be surprised. Signing on to do better and then conveniently ignoring that pledge while continuing to profit off of exploitation has been in the corporate food playbook for eons.

Take Cargill, for instance, a company that also made headlines for a commitment to end deforestation in its soybean supply chain. Instead of meeting its 2020 goal, it allowed suppliers to continue to clear acres of threatened forests in Brazil in the midst of a climate crisis and simply extended its own “deadline” further into the future. (Cargill paid its family owners record dividends last year after its profits increased 17 percent to a net income of $3 billion.) Or Arby’s, which committed to sourcing cage-free eggs by 2020 and then simply took the policy off its website and decided not to disclose its progress. Commitments to curbing greenhouse gas emissions are the next big curtain we’ll need to keep trying to peek behind.

To take it a step further, though, isn’t the idea of a “commitment” to eventually stop engaging in something as horrible and criminal as slavery or dangerous child labor a little insane? Or just downright silly? Either one? If a company says, “We’re trying to get child labor out of our supply chain but haven’t yet been successful,” what they’re really saying is that they’re not willing to sacrifice profits to fix it. And so far, no one is forcing them to do so.

It’s likely that the only truly effective (or at least the most effective) lever will be policy change. If the government said, “You can’t sell that chocolate here unless…” then things would be different. The Supreme Court decision could also have more lasting impacts. We’ll see.

In the meantime, eating chocolate is a privilege I recognize and enjoy (more than almost anything). And while I suffer no fantasy that my individual purchasing decisions will change the future of a global market worth over $100 billion, I don’t want to give my hard-earned dollars to these exploiters, especially not in exchange for something so pleasurable. So here are a few recommendations for rich, delicious chocolate made by companies that are truly doing things differently.

Tim McCollum, the founder of CEO of Beyond Good, is a thoughtful innovator. He explained to me—on The Farm Report last year—how he cut out all the intermediaries the larger industry relies on (AKA the reason big companies don’t even know where the chocolate comes from) and built his own supply chain. In addition to direct relationships with farmers, he says he pays farmers six times the industry average. The company also built a factory near its farms in Madagascar, where 75 percent of its chocolate is now produced. It’s an exceedingly rare approach, and it means more dollars stay in the country the cocoa comes from, since the entire operation now employs local workers.

Recently, McCollum spoke out about child labor. “The real problem in the chocolate industry is poverty,” he said. “The existing industrial supply chain keeps farmers living in poverty. No top-down protocol addressing symptoms, however egregious they may be, is a quick-fix for poverty.” In other words, with their complicated plans to “solve” child labor and trafficking, companies are blowing smoke at a fire fueled by low prices. Sea Salt & Nibs is my favorite, but all of the bars are delicious.

My editors at Civil Eats recently featured this small California-based brand on Civil Eats TV. I was excited to see it because I came across one of these bars a while back and was blown away by the flavor. Co-founder Karla McNeil-Rueda draws inspiration from her Honduran heritage to craft drinking chocolate and single-origin bars. Cru sources directly from farmer cooperatives—many of which are women-owned—in Guatemala, Honduras, and Nicaragua, and the team pays close attention to farm practices like pesticide use and seed diversity. I have not yet tried the drinking chocolate. Believe me, it is very high up on my to-do list.

As a New Yorker, moving to Baltimore felt difficult in some ways, and Jinji Fraser’s chocolate (and presence) made it easier. Fraser is a smart, talented chocolate maker who cares about each farmer she sources from, and lately she’s been using her voice to tell stories about how her Guyanese ancestry informs her work and purpose and how other BIPOC chocolate makers are shaping craft chocolate and navigating colonialism in the industry. Her Gianduja Fudge (dark chocolate fudge with wild hazelnuts) is wonderful, and so are the many “barks” she sells instead of classic bars. It used to be difficult to find these outside of the Baltimore and Washington DC area, but her team added online ordering and shipping in 2020.

Got others to add to the list? Comment, below.

A side of policy

Déjà vu or something new? On Tuesday, Tom Vilsack was officially confirmed to run the US Department of Agriculture. Vilsack also ran the department, which oversees both farm and nutrition programs, under President Obama. Groups that represent a wide spectrum of food and agriculture interests—from the National Corn Growers Association to Hunger Free America to the NRDC—applauded the move. But other progressive groups are still not happy about it. Food & Water Watch called the confirmation “a warning sign for family farmers and food and worker safety.”

Break it up. Earlier this month, Senate Democrats led by Amy Klobuchar (D-Minnesota) introduced a bill that would strengthen antitrust laws. Family farm groups are rallying behind it as one tool to address corporate consolidation and concentration in agriculture. Bryce Oates shares the details on The Daily Yonder.

Still hungry?

Garden renaissance. For Civil Eats, I reported on how seed companies are once again hustling to keep up with demand as more home gardeners plan for spring planting. It’s a very hopeful story about how the pandemic might inspire a new generation of home vegetable growers. And don’t worry, there’s no seed shortage!

Currently devouring

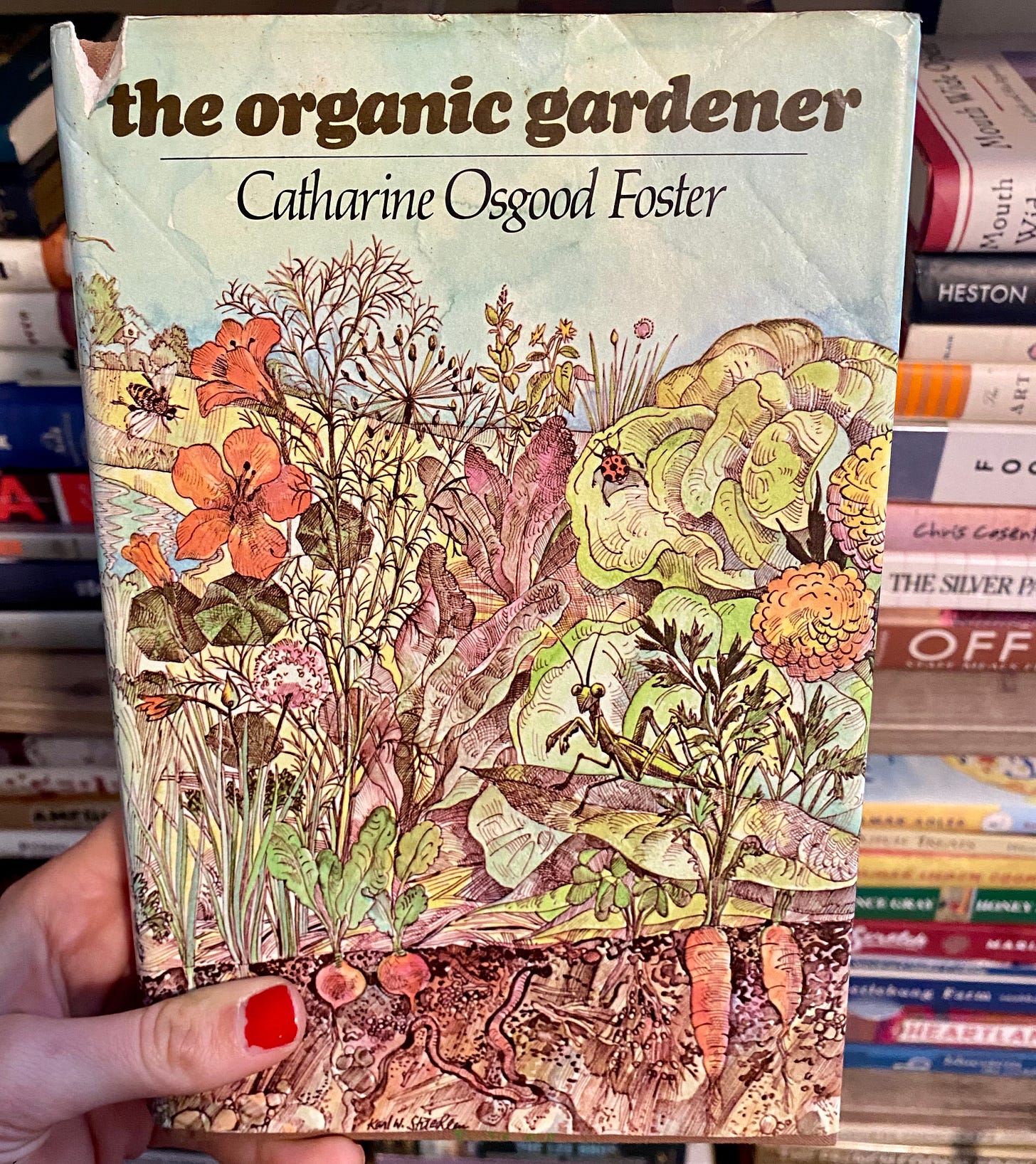

Speaking of gardening… I found this book from 1972 on a shelf and fell in love with it. Catharine Osgood Foster writes about how to grow food at home in a way that mimics nature’s complex, interwoven processes and how humans interact with them. She moves from the cellular structure of plants to how to read a seed catalog as if strolling through a breezy field and then offers beautiful, illustrated guides to mundane, practical problems like pest control.

Here’s a tidbit for you: “As you get become familiar with the way plants do their jobs, you get a sense of what they require and develop a skill in giving it to them if you can. Most important, you become aware of the entirety of a plant and of it its earth, warmth, and water environment. You get to know all its patterns and rhythms, and this is surely the secret of the green thumb.”

Actually eating

Unlike Joel Stine, the idea of a “lab-made dinner party” does not excite me, for many of the same reasons Alicia Kennedy brilliantly laid out in her newsletter last week. So my favorite part of the one Stine described in the New York Times last week was when he ran into Moby afterward (naturally) and the famous vegan wondered why anyone would eat cell-based meat when black beans and rice—what he called the “perfect food”—already exist. I would like to second that opinion and add a runner-up: fried rice.

Anytime you make rice, make extra. Then, you’ll have rice ready in your fridge a few days later. Old rice makes better fried rice, and with an onion, an egg, and whatever other vegetables you have in your fridge, you can transform it into a healthy dinner in 15 minutes flat. We eat variations on this constantly. This is a good foundational recipe, and then you can riff on it based on whatever vegetables you’ve got. (Last night, Spike made it again and added curry powder. It was great.)

Let’s be friends

Follow me on Twitter and Instagram to continue the conversation. See you next week!

I have been enjoying Peeled SO much, Lisa! I've passed it on to a few others as well who have subscribed and also had really positive things to say. As an avid chocolate eater, this one in particular really jumped out to me. Is there a way to tell if other brands are abiding by ethical practices? For example, I have several bars of Hu Chocolate in my pantry, and Stonegrindz is another brand I typically get. They tout single origin etc etc, but it's still unclear. It is safer to just avoid brands that don't explicitly say how they source their chocolate (because if they followed good practices, you'd think they'd want to promote that)?