Rooted in Atlanta

Truly Living Well is forging a path for equitable urban farmland ownership while serving and feeding local communities.

Just before the start of a three-day blizzard in Baltimore, executive director Carol Hunter texted me a video tour of Truly Living Well Center for Natural Urban Agriculture’s Collegetown farm. Deep purple Japanese eggplants and leafy green lettuces filled long, raised beds. A perfect sunflower swayed in the breeze.

The footage was filmed during a much warmer month. Still, when we spoke a few days later, as snow fell outside my window, her team was producing plenty of fresh, healthy food. “It slows down a bit in the winter, and we’re doing a lot of root crops,” she said, “but we’re able to keep food growing 365.”

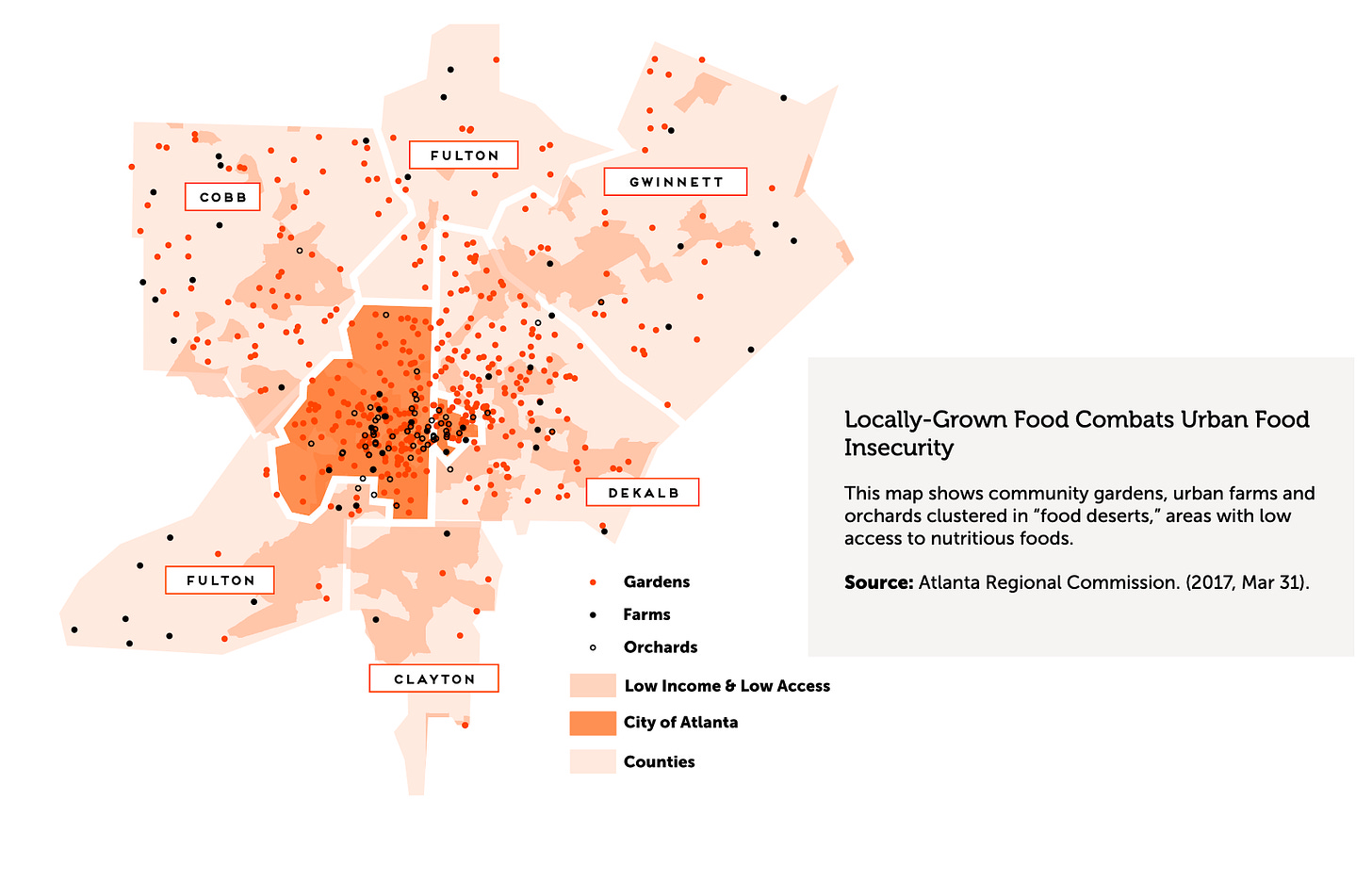

It’s one of several reasons, Hunter believes, that urban farming has grown so much in Atlanta, Georgia over the past two decades. Food Well Alliance is a local non-profit that was created to support that growth. In a 2017 report, it counted 52 farms, 300 community gardens, and 63 farmers’ markets in the five counties that include the city center and the most populous surrounding areas.

But Truly Living Well (TLW) itself deserves some of the credit for the beets-and-basil boom, said Kate Conner, Food Well Alliance’s executive director. Founded in 2006 by K. Rashid Nuri, TLW is one of the first farms to show up on the report’s timeline of agriculture in Atlanta. And the organization not only demonstrated the possibilities and potential of urban farming in its day-to-day work growing food, it focused on community engagement and education, including training farmers. “A lot of the farmers around the city have come up through Truly Living Well,” Conner said.

Now, the farm is forging yet another path. After over a decade of leasing various sites and almost four years of getting everything lined up to complete a purchase from the Atlanta Housing Authority, TLW now owns its land.

Among Atlanta’s urban farms, that’s exceedingly rare. “Land is very expensive,” Conner explained. “Most of our growers are leasing space, which makes it really difficult because they’re investing a lot of money into land that is not theirs and that can be taken away at any time. We have story after story from our growers who have this issue.” Stories from other cities around the country reflect that same reality.

Last week, I wrote about corporate ownership of farmland and had experts weigh in on what it meant. TLW’s story, I thought, is the perfect follow-up. It illustrates the real, on-the-ground challenges community farms face in putting down roots and what it means for them when they are finally able to. (I promise next week won’t be about land ownership!)

Before moving, TLW leased a seven-acre parcel of undeveloped land in the Fourth Ward for five years. When the owner decided to develop that land, the organization was told to vacate. With the help of a network of community partners, they found the Collegetown plot and leased it from the Atlanta Housing Authority.

But if moving your belongings from one small apartment to another has ever driven you nearly to the point of madness, you can begin to imagine what it means to move a farm.

“It was a huge undertaking,” Hunter said. “When we left, we took all of the compost that we had built, tons of healthy soil. We took over 100 fruit trees that we had in the ground. We literally had these huge spades that picked them up, drove them over to Collegetown, and put them right in the ground again. It took us several months to do all of that.”

Thankfully, they received a warm welcome from residents in the new neighborhood, who volunteered to help them clear parts of the three and a half acres and fill raised beds. “That was significant for us because we knew that this community was one… that does not have access to fresh, healthy food. And so we knew that this could be a life-changing situation for that community,” she explained. In fact, that’s part of the reason the Housing Authority was willing to lease—and later sell—them the land.

“Truly Living Well supported our Choice Neighborhoods mission to bring about transformation in the Ashview Heights neighborhood, which is a USDA-designated food desert,” James Talley, an executive at Atlanta Housing said in a press release. “They provide a space for local food production and connect residents to healthy food resources and educational opportunities. I cannot understate the value they’ve brought to the community.”

Now, the next chapter begins.

For Hunter, ownership of the land has both philosophical and practical implications, all of which are intertwined. It starts with the fact that TLW is a Black-founded and Black-led organization. Over the past century, Black farmers in the US have lost 90 percent of their land, due to land theft, racist policies, and economic inequality. “That's the number that needs to be turned around. To be able to say we own land is very important to our story. When we talk to people about land ownership now, it's not just talking. We're actually demonstrating what we can do with it.”

Suddenly, Hunter’s team can work on long-term planning for growth and make real investments in infrastructure that will directly benefit the organization and surrounding community. “It changes your mindset and how you approach this work. It's not just season to season, it really is: How, over the long-term, can I continue to develop the space in such a way that we're maximizing our ability to grow food and be transformative to this community?”

They’re starting to work with both an elementary school and a high school in the neighborhood. One of their produce markets now takes place on the farm. They’ve built a greenhouse, an aquaponics lab, and a community compost lab, the latter with help from partners, including Food Well Alliance. The compost program, Hunter said, will demonstrate “full circle” solutions. “We grow the food, we sell the food, we distribute the food right back to the community, and then the community brings the waste back to the farm. And we're able to take all of that and turn it into healthy soil that goes back into the beds.”

On a single piece of land well cared for, natural processes can turn waste into food and habitat, while the dedicated work of farmers can transform lives beyond the fence. According to Hunter, “We’re not very far from the expressway, but by having that farm and those trees right there in that area of Atlanta, we’re actually changing the ecosystem.”

Still hungry?

“If you’re after getting the honey, then you don’t go killing all the bees.” That’s a line from one of (my partner) Spike’s favorite songs, Johnny Appleseed by Joe Strummer. It was playing in my head pretty much the entire time I was reporting this very long, comprehensive story on neonicitinoids (or neonics, for short). Neonics are now the most widely used insecticides in the world, and they’re bad for bees. My story looks at how we’re increasingly learning that they’re bad for, well, pretty much everything else too. I also survey the policy solutions being proposed and whether or not they might go anywhere. It is very rare that I feel proud of a story; this is one of those rare occasions.

A side of policy

Pandemic probe. A congressional panel is investigating three of the country’s largest meatpacking companies—JBS, Tyson, and Smithfield—to determine if COVID-19 outbreaks at plants were the result of safety violations. Senators Cory Booker (D-New Jersey) and Elizabeth Warren (D-Massachusetts) conducted a similar investigation several months ago, but as Leah Douglas points out, the panel will have the power to subpoena documents.

Restaurant relief? Restaurants and the workers that run them have been hit unbelievably hard by pandemic shut-downs, with one in four jobs lost occuring in the food and beverage industry. So far, the government has largely ignored that fact. (Past relief bills have offered small business aid which has helped some, but nothing specific to the industry.) Now, House Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-California) and Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer are pushing to include a $25 billion “independent restaurant revitalization fund” in the next round of relief. The Independent Restaurant Coalition praised the measure, even though they’ve pushed for $120 billion.

Meanwhile, this caught my eye: Spain’s government is requiring landlords to cut restaurants’ rent by 50 percent throughout the state of emergency. And they’re giving the landlords a tax cut to make up for it. It seems like such a simple, effective strategy. Way too much common sense for the US, maybe?

Currently devouring

But at least this will make you laugh…This satirical statement from the designer of restaurants’ outdoor seating, in McSweeney’s, had me in tears. “ I have used materials traditionally reminiscent of an indoor structure, such as four walls and a roof and a door, but playfully recontextualized them in the quintessentially outdoor environment of the middle of the street.” It’s important to laugh to keep from crying, people.

Faux fix? There are plenty of smart (and stupid) arguments to be made in favor of techy meat replacements, but the numerous to be made in opposition are not nearly as prevalent. In this reported op-ed, Charlie Mitchell skillfully details a fundamental truth about the Beyonds, Impossibles, and Justs of the world: “Mimicking the meat giants, aspiring to their mammoth production and monopolistic tyranny, is to build a “new” industry in the image of the world’s ugliest business.” Whether you agree with his conclusions or not, it’s crucial to understand who and what is driving these corporations. And it’s especially relevant this week, when the “good” news of fake meat getting cheaper is everywhere. Wait, I think I’ve heard that somewhere before?

Speaking of spin… Oil and gas companies practically invented the art. In Heated, Emily Atkin investigates how fossil fuel giants are creatively mounting opposition to the Biden administration’s climate agenda. In some cases, it’s as simple as getting around Twitter’s ban on political ads by not referencing actual policies.

Actually eating

I missed our weekly farmers’ market a few weeks in a row for various reasons, one of which was that I wasn’t really itching to go…because this time of year it can be pretty bleak. (As in, no, I don’t want to only eat old squash for four months.) But I was totally caught off guard by how much more inspiring it was compared to the grocery store—even in the dead of winter as a snow storm approached.

I got beautiful organic spinach, cabbage, and orange and white sweet potatoes. Also: vibrant, nutrient-dense microgreens, hand-made feta and goat cheese, and storage apples. I know I’m being super earnest right now and my list sounds like it came out of a Portlandia epsiode, but hey, it happens. There are so many people who talk about how much more convenient buying produce at the grocery store or online is, and I want to shout: But have you tasted this stuff?! It’s so worth it. P.S. Maybe you’re thinking it’s expensive? I’m working up to an entire issue on the cost of “good” food.

Let’s be friends

Follow me on Twitter and Instagram to continue the conversation. It is a challenge for me to engage on Twitter, but sometimes I say riveting things like this:

See you next week!