Extra virgin olive oil should make you cough

...and other interesting insights on the healthy staple—from farm to bottle.

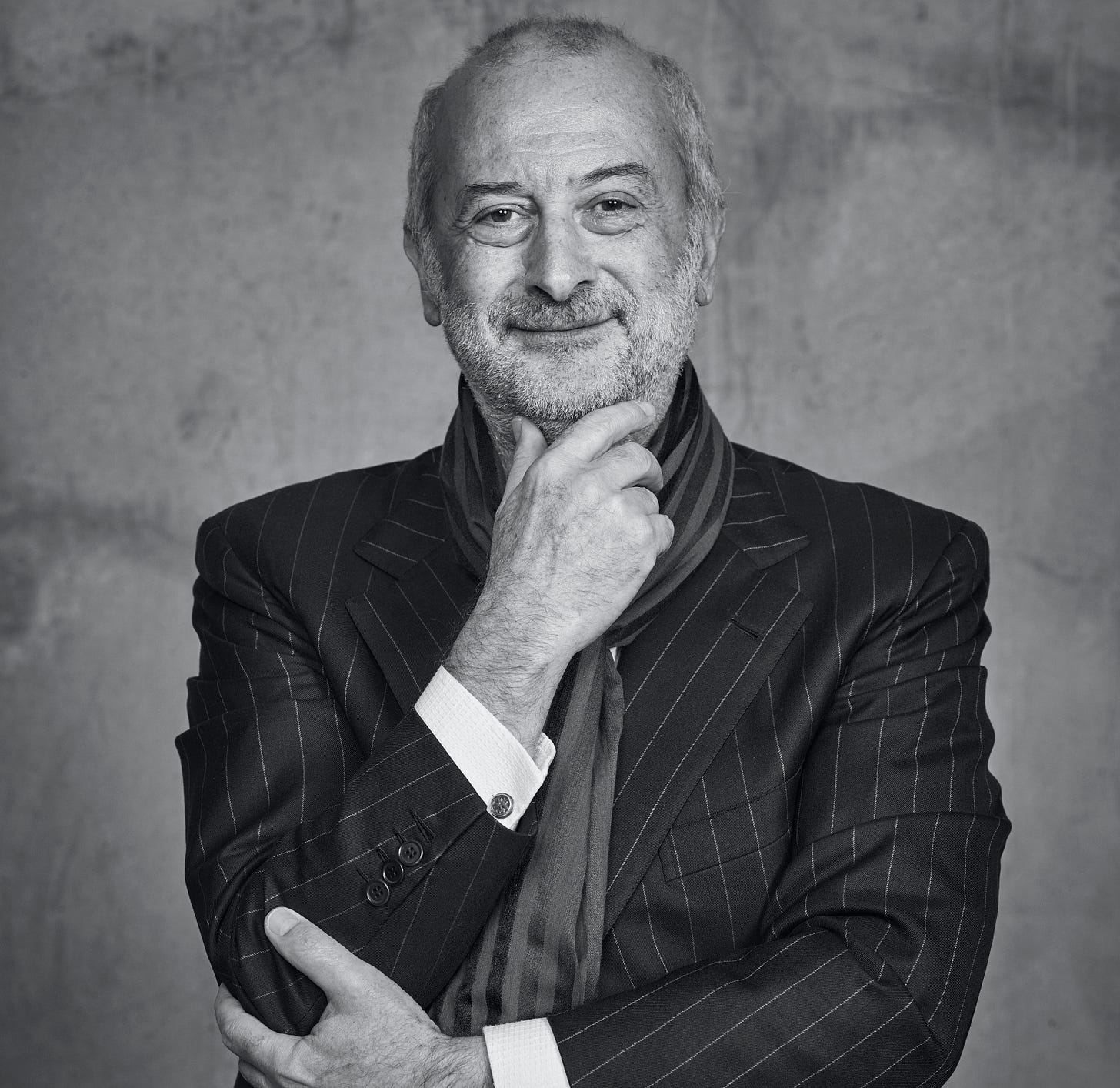

Armando Manni is so obsessed with the quality of his extra virgin olive oil, he has researchers at the University of Florence test it every four months to measure its antioxidant power. That’s not exactly the norm.

While there are plenty of other producers making top-tier oils (especially in Tuscany), the global olive oil industry is filled with mislabeled, highly processed products that don’t deliver any of the benefits people believe they’re paying for.

Of course, price is part of the issue. Unlike those cheap bottles, MANNI oils are not the everyday products average individuals can afford to use at home. They are primarily used by top chefs in Michelin-starred restaurants and by the Hollywood elite (thanks to Manni’s career as an actor), and while a new product, The Oil of Life, is about 30 percent cheaper, it would still be a splurge (i.e. great gift) for most people.

I generally avoid covering foods that feel like luxury products, but I decided to interview Manni as a guest on The Farm Report because his passion for quality means he has spent two decades digging deep into the processes that result in really good olive oil. He can speak to how to maximize antioxidants in the oil starting with the trees in the groves, for example, and to preserving those health-boosting compounds so individuals using the oil continue to benefit years later.

In this interview, we also get into how the pests that plague olive groves make organic practices difficult and how climate change is exacerbating that issue while also affecting harvests. Finally, he offers smart tips on how to shop for and taste extra virgin olive oil, regardless of the brand. Starting with: It should make you cough (during tastings, not when drizzled on your pasta).

If you’re interested in hearing me coughing loudly into a microphone, you can listen to the full interview on The Farm Report on Spotify, Apple, or Heritage Radio Network’s website. If you prefer the highlights, keep reading below for an edited, condensed version of the interview.

Unwrapped

Why did you start making olive oil? What drew you to it? I started making the oil for my son. I was a film actor at the time; I won the Golden Globe here in Italy. So we are talking about more than 20 years ago, and I started to make the oil for him, because I’m a foodie. And the only thing it was not possible to find here in Italy—it’s strange to say, but it’s true—was an oil that was certified on every level, including traceability, but also...

I don’t think people are aware that the moment you buy a bottle labeled “extra virgin olive oil,” by the law, you are not buying extra virgin olive oil, you are buying an olive oil that at the moment of the pressing, exactly in that moment, has been declared extra virgin by the way that it has been pressed. The olives have been pressed mechanically and then the juice you’re getting is analyzed and is matching the chemical parameters that define the commercial category “extra virgin olive oil.” [As opposed to “virgin olive oil” or just “olive oil.”]

Now the problem is that this is true at the moment of pressing, but everything in the world is oxidizing. My skin, I make wrinkles when I oxidize. Fish becomes bad smelling after one week...if you don’t put it in the fridge. The same is happening to olive oil, and the problem is you don’t know when you’ll arrive at an oxidation that will destroy all the health benefits and transform the extra virgin olive oil into simple virgin olive oil or even olive oil. Because of that, my ambition was to create an oil that was very stable, for my son. In fact, the first oil we produced in 2001 was Per Mio Figlio, which means “for my child” in English. Then I started to gift it. I was having my agent in Hollywood, so I was flying constantly between Rome and California, always stopping in New York because it’s a very long flight. And in New York, I gave a taste of the oil to Jean-Georges Vongerichten, because I was a client. He ordered to me 800 bottles, and I was not prepared for that. So I created a company, I created a production line, and I started to sell the oil...and the adventure started. I took a sabbatical, and I’m still on sabbatical 20 years later.

So, it all started with this idea of preventing oxidation. I’ve read that one of the ways olive oil producers do that is by harvesting the olives earlier so that there are more antioxidants in the oil. Is that part of your process or are you doing something else differently? Well, there is a lot more. When we did start our production, we were harvesting a month and a half earlier than the tradition here in Tuscany. So, that’s a lot. The quantity and quality of the antioxidants—by the way they’re called polyphenols—depends on several factors. One is the cultivar; the cultivar is the kind of olive trees. You have in Italy something like 57 different cultivars. Like a rose, think about how many roses we have. The same is for the olives. This is one thing.

Then, we are organic; we are also biodynamic.

The quality of the work you do on the ground and on the trees is very important. We say the olive tree is a gentleman. If you are very polite and take proper care of it, he will give to you everything back.

We also did it in conjunction with the University of Florence, and our oil is the only in the world that is produced...inside a scientific research project that also certifies us our extra virginity every four months, because coming back to your first question: You buy a bottle and you don’t know if it’s still extra virgin at the moment of consumption.

You mentioned the groves are organic. I looked around and there aren’t many high-quality Tuscan olive oils with a certified organic label on them. Why not? Is it just a matter of certification in some cases, or are there very big differences in your production compared to other producers in the region? Well, it’s very difficult to be organic because you can’t use any chemicals on one side to support your olive trees and on the other side to defend your olive trees. We are under climate change, and climate change is changing here the kind of bacteria we have, the kind of parasites, and so on.

So, there are a lot of problems, and of course the biggest enemy we have is a traditional enemy: that is the so-called fly of the olives. It’s a fly that puts its eggs inside an olive. To fight this, it’s very difficult for an organic farmer. A common farmer can use a lot of chemicals, but they are very poisonous. For us, it’s a very delicate process. We use only organic products. Some of them are experimentation...so we can save the quality of the olives. Because otherwise, when you press the olives with the eggs inside or with the baby flies inside...you’ll have a terrible oil with a very bad smell. This is a problem that is affecting so much of the olive oil production in California. That’s the reason you don’t find so much organic olive oil in California. But you can do it. One of the secrets we have is that we’re on a slope of a mountain. Our olive trees are in a very high position, and this is helping us to not have the invasion of the flies that prefer to stay in Tuscany on the flat lands or the border of the sea, where they can find a much better environment.

That’s really interesting. You mentioned the changing climate causing an increase in pests. Have you seen impacts in your groves yet in any other ways? For example, I’ve seen a lot about olive harvests being affected by climate change, but then I also saw that in Tuscany, 2020 was the best harvest in a very long time. Can you talk a little bit about what you’re seeing? Climate change is for sure impacting the quality of the extra virgin olive oil because most of the time we’re having dry summers. This is impacting wine also; wine is suffering from the same problem. And you can see that the production is going up and down in a very violent way between one year and the following year. So it’s difficult for you to plan, to make commercial deals. You never know how much oil you will be able to produce. Last year has been a very good year, but a very good year in terms of quantity. In terms of quality, not many made a great oil.

Is there anything that the industry is doing or that you’re doing to prepare for the changes in weather? For instance, is there anything you can do in the groves to build resilience? I think in terms of industry, no. In terms of private people and companies, for sure someone is doing something. As you were mentioning before, one thing is to harvest earlier and earlier and earlier. But...you have a limit, because in an olive, you have a quantity of polyphenols and a quantity of oil in the fruit. What is happening is that the more the fruit becomes ripe, the more oil you have inside but the less polyphenols you have. So [if you harvest too early], you’ll have a very small quantity of oil and a lot of antioxidants, but there are so many polyphenols, you have the feeling of eating roots. It’s very rooty...because the percentage of polyphenols is an enormous percentage of the oil.

Let’s talk about the harvest process. Your website describes it as “sustainable harvesting.” I’m curious about what that looks like. Is it a mechanical process? Can you describe it? Well, our process is sustainable starting on the ground and ending with the bottling. We are the only olive oil mill in the world that is working with a circular economy. This means we don’t produce any waste. Everything is upcycled, not recycled. So we transform our waste into something that is fantastic, because it’s a magic powder. It’s an olive powder that is a concentration of antioxidants and is terrific [for] anti-aging. I personally use it every day. Now chef Thomas Keller is doing some experiments to make antioxidant and anti-aging bread…with our powder.

So the powder is made from the mash [the olive pulp leftover after pressing, called pomace], that’s left over? Yes, the leftovers. But then coming back to your question, we harvest by a special machine that [resembles] a sort of hand. So, every worker has these hands that are going through all the leaves to not offend the tree and [shaking] down the olives on our net. Then we process our harvest in two, three hours. It’s very important because the moment you take out the olive from the tree, the olive starts to be bombarded by bacteria and so on. It’s important that you harvest and you press...as quickly as possible. There are people who put the olives under the sun, they wait. In the past, in the tradition, the people were waiting even two days because in two days, the olives were losing some water, so when they were pressing, they were getting, for every kilo of olives, more oil.

After pressing, what are the big factors that impact oxidation? Three things increase oxidation of the oil. One is UV rays. So, never never buy a bottle of extra virgin olive oil in transparent glass. In two months, the light, the UV rays will kill all the polyphenols inside, and you will lose all the benefits of the antioxidants, and the oil will turn from extra virgin to virgin. Then oxygen. This is another big point. Oxygen is feeding oxidation. Never buy a big bottle. You buy a big bottle that will be standing in your kitchen for days or weeks with all this oxygen going in your bottle every day. You have a third enemy that is temperature, hot temperature. In general, people are leaving a bottle of oil close to the gas machine, where you have fire, and in the kitchen, which is the hottest room of the house. [You also want to avoid oxidation] because the polyphenols are responsible for the taste and the smell of the oil. 95 percent of the composition is fat cells; that doesn't have a smell or a test. The smell and the taste and the flavor is coming from the five percent, called minor components, the polyphenols.

I wanted to ask you about the bottle transparency issue. It seems so simple, so is it cheaper to bottle in clear glass? I don’t understand why else any company uses a clear glass bottle if that’s such an obvious factor in terms of maintaining the quality. Well, if you are talking with some marketer for multinationals that are invading the market with these kinds of bottles for a very cheap price, they will tell you, “we do transparent bottles knowing that the UV rays will kill the oil, but we do that because people want to see the nice green color. And this will be reassuring for them because they will feel like they are buying something natural.” Well I have to tell you something: The oxidation is enormous in an oil that is super green, because super green means there’s a lot of chlorophyll inside, and the chlorophyll is feeding a lot of oxidation. Another thing feeding oxidation is when it’s not filtered. Never buy an unfiltered oil. It doesn’t mean the oil is more pure, it means there is more mud inside.

Okay, how does one go about properly tasting an olive oil? You never taste olive oil with bread, that will make every oil the same as the other.

How to taste the oil: first of all, take a small cup and pour the oil in there. Hold the cup with your hand because the point is to transfer the heat of your body to the oil that is inside the small cup. It’s important that with the other hand you close the cup, because you want to create a vacuum so the air that is inside the cup should not go out. Moving the oil inside the cup, you will feel at a certain point that the cup is not cold anymore but it reached the same temperature as your body.

At that point, take away the other hand and smell it intensely and think about colors. This will help you to drive your mind through the colors to something that is more familiar. Maybe it’s green that’s green like grass just cut or maybe it’s yellow, yellow-green, or brown because it makes you think about roots. After that, you can sip it, but you have to sip a real sip, like you would do with a wine, [taking in] a lot of air...something that makes a lot of noise.

There was an old English journalist who was saying an extra virgin olive oil is not great if it doesn’t make you cough at least twice. So if you breathe properly through the mouth, sucking in the air, having the oil in the mouth, you will see that if the oil is still extra virgin, it will make you cough. And then you will have a lot of feelings in your mouth, but if the oil is still extra virgin, the feeling you will never have—never never—is greasiness. The only greasiness will be on your lips. That’s important. So you are eating something that is fat, but it’s making your mouth incredibly dry. Why? Because the polyphenols. They’re cleaning the mouth from the fat.

Wrapped up, to go

*Many factors influence oxidation in extra virgin olive oil, from the type of olive tree to the speed of pressing to the bottle itself.

*Manni’s tips: Buy oil in dark bottles and minimize the oil’s contact with heat and oxygen to maintain the quality. When you taste a true extra virgin olive oil, it should make you cough a little and shouldn’t feel greasy in your mouth.

*Climate change is making olive harvest more unpredictable and increasing pest pressure on producers, making it harder for them to avoid chemical pesticides.

A side of policy

Pandemic payments for food workers? For Civil Eats, I covered the USDA’s announcement on Tuesday of a new program that will offer $600 relief payments to individuals who worked on farms and in meatpacking plants throughout the pandemic, putting themselves at risk (while also facing financial hardships in many cases) to keep the food supply stable. I talked to people who represent food workers on the ground to find out what they think of the announcement, especially given USDA has a long history of handing out cash to farmers but almost none when it comes to supporting those who work for those farmers.

Currently devouring

When Bayer is your BFF…of course you’re going to want to help get one of its herbicides back out there, even after millions of acres of crops have been damaged. That’s essentially what happened at the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), according to a new story from Investigate Midwest, in which a reporter reviewed federal documents showing the powerful agrichemical company was in (really) close contact with the EPA as it attempted to re-register dicamba to get around the court order.

Actually eating

I found a lot of joy in the kitchen this week, fueled primarily by embracing the end-of-summer produce. One of our favorite fruit farmers (Black Rock Orchard) gave us a whole bag of overripe plums he was going to have to toss (because we got to the market 10 minutes before closing time, as usual), and I quickly made a version of this plum cake so they wouldn’t rot. It was so easy and delicious, but I forgot to take a picture. I also made pesto with a big bouquet of basil and baba ganoush (thanks, Erin!) using a particularly plump eggplant. And of course…

Tomato sandwiches. The simplest summer treat, soon to retreat. Bread, juicy tomatoes, mayo, salt, pepper.

Let’s be friends

Follow me on Twitter and Instagram to continue the conversation. See you next week!